Heath Joske

Story by Alex Mitcheson Photography Supplied by Patagonia

The early 2000s was a transitional but pivotal era for popular culture. Reality TV was born, Facebook flourished, and climate change was an off-the-cuff phrase from late night news shows slowly becoming everyday vernacular. During this time, the world of competitive surfing was at its peak, riding a surge of popularity and excess from the 90s into a new millennium where magazines and surf movies presented flashy vignettes of an aesthetically pleasing lifestyle to the masses.

From honing his grommet zinc-covered talents on the manicured sandbanks and pointbreaks of Valla Beach, Heath Joske found himself on the carousel of surfing’s World Qualifying Series. Coming from a quiet, pristine corner of New South Wales and then jet-setting from one densely populated surf zone to another was a regime he found difficult to harmonise with.

“Three quarters of the year, we were on the road chasing contests all over the globe. I was eating out all the time, getting everything given to me, constantly eating on planes where everything comes wrapped in plastic,” sighs Joske.

A world removed from a discernibly different childhood? “As a family growing up, we’d travel around the coast — but we’d always have our food and water packed. Seeing this consumption involved in travelling and competing was pretty confronting.”

Before the start of each competitive year, Joske and some mates would take themselves off the radar and down to South Australia. The expansive Eyre Peninsula is a tangle of arid scrub juxtaposed against an expanse of stirring teal ocean. A place at the edge of the world where nature walks a fine line. Dazzlingly beautiful and relentlessly antagonistic in the same breath.

Joske would meet his partner in Streaky Bay on one of these trips, and as his world began to turn faster, the

call to settle in this part of Australia became too loud to ignore. Apart from falling in love the conventional way, his admiration and affection for the landscape and climate in this southern extremity came into its own. He admits, “I’d come down here and have time away from competing devoid of luxuries, people, and the pressure of contests. I found I was enjoying myself more.” Between no phone reception, little distraction, and lots of downtime, the East Coast surfer knew this was where he wanted to call home.

It’s a place not exactly swarming with people, though. You’ll be hard - pushed to find any badly parked Range Rovers, crowded cafes, or rush hours here. And it’s far removed from the sub-tropical pastures of the mid-north coast. The locality and weather don’t make it people’s first choice as a place to live off the grid while pushing the boundaries of self-sufficiency.

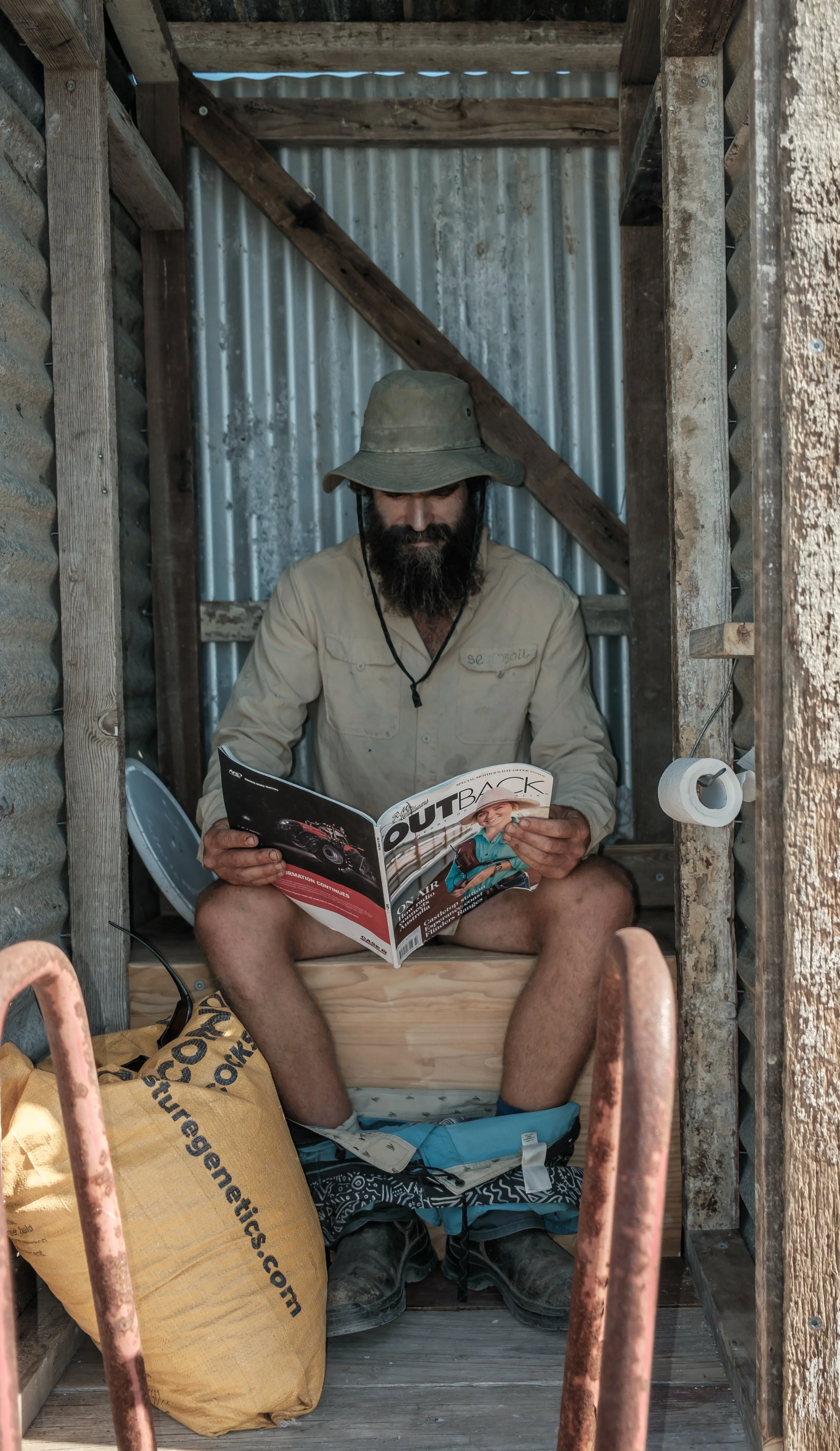

Be that as it may — and now, with two kids in tow — the Joskes’ residence is on a prime patch of dirt that bears their stone built home, countless vegetable patches, beehives, chickens, and an ingenious humanure composting toilet directly feeding a collection of fruit trees. As a Patagonia ambassador, Heath has recently been the star of a mini - series produced by the B-Corp, a planet-changing behemoth called Farm Boys. The six-part hardcore surf and gardening show is a snapshot of living sustainably, featuring friends and family, impassioned upcycling, and the magic of living a simple life.

But it hasn’t all been plain sailing. “I tend to just jump into things headfirst and learn from my mistakes. I’m a terrible builder, but I’m slowly learning. I’m a terrible stonemason, but I’m getting a lot better. I was a terrible gardener, but I’m okay now. Every day, there’s something fresh going on,” he says. After seeing his first crop of 20 fig cuttings and olive and mulberry trees all die within months, it was the impetus needed to look a little deeper and consider the health of the soil.

Five years in, the knacks of worm farming, composting, and mulching are environmental arts Joske regularly practices — and with great success. It’s complex, but at its core is a simple system: household greywater feeding worms, who then break down food scraps and garden waste, creating an all-you-can-eat buffet for plantings of fruit and vegetables. The finale, however, and what closes the loop, comes from the Joskes themselves — with straw and time, this too becomes an invaluable elixir.

“Watching your waste turn into garden gold is an incredible cycle to be part of. You’re the reason the waste feeds the soil that then, in turn, feeds us, and so being the catalyst towards why the circle keeps turning. It’s the best”, smiles Joske.

What they don’t eat themselves ends up at the end of the drive in a quintessential produce stall complete with honesty tin. Beside reads a sign inviting charitable donations of fish scraps. Strange? Not really. What other eco-friendly way are you going to give your egg-laying chickens protein?

Another facet of living such an autonomous reality is seeking opportunities to repurpose unwanted machinery, discarded materials, and broken everyday items. Joske’s green-fingered confidant, Tim Addy, is featured across the online series: part modern-day hermit, part dirt whisperer, part surfboard shaper. Addy’s years of experience growing produce and composting are undeniable. Still, it’s his fun filled approach to jumping around piles of junk and seeing the potential for anything and everything to have a brand new function that captures the imagination. It’s the epitome of optimism and resourcefulness rolled into one. The result is that these salvaged materials have allowed Joske to build fundamental structures across his property, from fences to chicken sheds, with little to no cost. Joske muses, “there’s a beauty to working with recycled supplies. There is an inherent art when you’re exposed to building or putting something together with used materials. It’s functional art. It doesn’t take long to get comfortable tackling little projects by yourself. Plus, you end up with something — like a piece of furniture, say — which isn’t poor quality and will last.”

So where does surfing fit into all of this, or has the dirt ultimately won him over from the ocean? “Doing what I’m doing on our little farm is taking up a lot of my time — which I’m happy for it to do. I wake up excited about making compost, planting trees, or fertilising vegetables! These days, it’s a release that I need every so often, whether three times a week or once a fortnight. It’s pretty healing for me mentally.”

Both are very singular environments but intrinsically regulated by nature. On balance, the winds, rains, sunshine, tides, and swells are variables well outside the remit of even the most steadfast gardener or veteran surfer. “Learning the intricacies of either pastime can be a lifelong journey”, smiles Joske, “Being observant for changes and anticipating what might come next is key. It’s a transferable skill for both pursuits and keeps you on your toes.”

Hectic lifestyles rule our world. If we’re not taking ourselves to appointments and engagements, there’s now an underlying necessity to keep abreast of other people’s lives across social media. Notifications light up stealing away our attentiveness at any given moment. Interestingly, Joske has found himself in a parallel situation, except the announcements grabbing his attention are not pictures of somebody’s lunch or clearance sale emails. Instead, they’re from nature soliciting him to add more water here and prune back a touch there. “The sad reality is most people are so disconnected from nature. Rural life is simple, but it provides you with a beautiful routine. Most people go from their homes to cars to work and back again with barely any time spent outside. Growing any food — even if it’s just a balcony herb garden — requires diligence and harbours an appreciation for nature,” he says. However, in nature, there is no Do Not Disturb mode. A poignant reminder the earth wants kindness from us, but at the same time, it needs our understanding. “Growing your own food drives home how extremely fragile she can be, too. Connection to the environment and grasping its delicateness is imperative for the future of our planet.”

If you’re interested in seeing more of our work - we hope you’ll consider subscribing to our physical paper here.